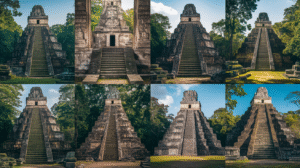

Belize is celebrated for its extraordinary collection of ancient Maya sites, showcasing the highest concentration of these archaeological treasures in Central America. With over 1,400 documented locations, these sites span an extensive timeline of more than three millennia. From the awe-inspiring riverbank temples at Lamanai to the towering pyramids of Caracol, each archaeological complex offers profound insights into the sophisticated aspects of Maya statecraft, religion, and the daily lives of the Maya people. This comprehensive guide will explore nine essential ruins that you must visit, provide practical travel planning tips, and deliver the cultural context necessary for a fully immersive experience of Belize’s archaeological wonders.

Uncover the Reasons Why Belize is the Epicenter of the Ancient Maya Civilization

The rise of the Maya civilization in present-day Belize can be traced back to at least 2000 BCE, flourishing robustly until well into the Spanish colonial era. This civilization thrived due to the fertile river valleys, especially along the New River and Belize River, and its advantageous access to rich marine resources from the world's second-largest barrier reef. Moreover, an intricate web of trade and political alliances bolstered their economic strength. Today, the Institute of Archaeology, part of the National Institute of Culture and History (NICH), oversees 14 official archaeological reserves, many of which are located within or adjacent to UNESCO World Heritage sites. Their ongoing work, combined with decades of academic research, reveals how Belizean Maya communities significantly impacted regional history.

Embark on a Journey to Explore the 9 Must-Visit Maya Ruins in Belize

Discover the Maritime Trading Centers of Northern Belize

Lamanai: “Submerged Crocodile” – The Longest Inhabited Maya Site

Lamanai, originating from the Yucatec Maya term Lama’anayin, translating to “submerged crocodile,” is strategically situated alongside the banks of the New River Lagoon and boasts a remarkable history of occupancy extending from the 16th century BCE to the mid-20th century CE. This site was a pivotal trade center, forging essential connections between inland communities and coastal merchants. Visitors often arrive by boat from Tower Hill, where they can explore the stunning Mask Temple, featuring a striking 2.7-meter stucco mask that represents the rain deity. Furthermore, the Jaguar Temple and the High Temple rise majestically above the lush jungle canopy. Ongoing archaeological excavations conducted by NICH have uncovered residential courtyards, a ballcourt, and substantial evidence of trade involving jade, obsidian, and ceramics, highlighting the site's historical significance (Institute of Archaeology, NICH).

Altun Ha: “Rockstone Water” – The Historic Site of the Jade Head Discovery

Located approximately 50 kilometers north of Belize City, Altun Ha, which translates to “rock water,” garnered international fame in 1968 when excavators from the Royal Ontario Museum unearthed the astonishing 4.42 kg jade head of Kinich Ahau. This artifact is recognized as the largest carved jade object from the Maya civilization and is now displayed at the Museum of Belize (Royal Ontario Museum). The site features the impressive 16-meter-tall Temple of the Masonry Altars, providing a panoramic view over ancient trade routes that historically connected inland polities to Caribbean ports. Interestingly, unlike many other Classic-period centers, Altun Ha lacks inscribed stelae, indicating that its elite preferred monumental sculptures over hieroglyphic inscriptions (Pendergast 1979).

Santa Rita: A Site Demonstrating Late-Period Cultural Contact

Positioned near Corozal Town, the Santa Rita site remained an active settlement well into the early colonial period. Artifacts discovered here, including ceramics and Spanish-era items, capture the adaptations of the Maya to European influences and contact. Furthermore, the nearby Cerros site, linked by a network of causeways, underscores the economic resilience and evolving trade networks of northern Belize during the late period (Awe 2005).

Investigate the Political Powerhouses of Western Belize (Cayo District)

Xunantunich: The “Stone Lady” Legend and the Majestic El Castillo Pyramid

Nestled on a prominent bluff overlooking the Mopan River, Xunantunich, meaning “Stone Lady” in the Mopan Maya language, features the iconic El Castillo pyramid, which reaches an impressive height of 43 meters. Visitors must first cross the river via a hand-cranked ferry before making their way through the jungle to reach this remarkable site. Upon arrival, they can admire an astronomical frieze that illustrates the cycles of the sun god and Venus. Local lore speaks of a spectral figure, often described as a white-robed spirit, seen atop the central plaza, adding an intriguing element of mystery to the site (Chase & Chase 2015).

Caracol: The “Snail” – The Largest Maya Site in Belize

Spanning over 200 square kilometers, Caracol reached its zenith around 650 CE, boasting an impressive population of approximately 120,000 inhabitants, positioning it as a formidable rival to Tikal in terms of power and scale. The site’s Caana (“Sky Place”) temple towers at a remarkable height of 43 meters, making it the tallest man-made structure in Belize. Throughout the site, over 120 carved stelae document dynastic victories, including the notable conquest of Caracol over Tikal in 562 CE, while inscriptions provide invaluable insights into the political history of the Maya civilization (Chase & Chase 1996). Additionally, advanced agricultural techniques and hydraulic systems reflect the sophisticated urban planning that characterized Caracol.

Cahal Pech: “Place of Ticks” – A Royal Acropolis Complex

Cahal Pech, which translates to “place of ticks” in Yucatec Maya, is situated atop a ridge that offers a panoramic view of San Ignacio. As one of the earliest civic-ceremonial centers in Belize, dating back to approximately 1200 BCE, the site features limestone palaces and ballcourts that exemplify early Maya architectural styles. Its convenient location near the town makes it an ideal destination for families and visitors seeking a gentle introduction to the rich history of Maya ruins (Powis et al. 2010).

Unveil the Unique Architectural Styles of Southern Belize’s Maya Sites

Lubaantun: “Place of Fallen Stones” – Renowned for Its Mortarless Construction

Nestled within the misty hills of the Toledo District, Lubaantun is distinguished by its unique black slate masonry, constructed without mortar through clever “in-and-out” techniques, resulting in a striking stepped appearance. The site includes three ballcourts and numerous burial caches, suggesting its significant ritual importance. Additionally, it is here that the infamous crystal skull reportedly emerged in 1924, though scholars continue to debate its authenticity and origins (Mitchell-Hedges 1998).

Nim Li Punit: “Big Hat” – Home to Belize’s Tallest Stela

Also located in the Toledo region, Nim Li Punit features 26 intricately carved stelae, the most prominent being Belize’s tallest monument, depicting a king adorned with a towering “big hat.” The stelae plaza is believed to have served as an astronomical observatory, marking significant equinox alignments, demonstrating the Maya's advanced understanding of astronomy (Helmke & Awe 2016).

Uxbenka: Recent Excavations Uncover Astronomical Alignments

Since 2015, excavations at Uxbenka have revealed temple platforms meticulously aligned with the solstice sunrise, showcasing the remarkable astronomical knowledge that the Maya possessed. Situated near the Guatemalan border, this rural site provides pristine exploration opportunities and offers valuable insights into the political dynamics of Classic-period southern Maya societies (Smithsonian Mesoamerican Research).

Key Tips for Planning Your Unforgettable Maya Ruins Adventure

Transportation & Access:

Reaching most Maya sites requires ground transportation. From Belize City, daily bus services or private shuttles transport visitors to San Ignacio and Corozal; from these locations, various tour operators offer 4×4-driven site visits. Notably, accessing Caracol involves a 16 km journey along unpaved roads, which can become impassable during heavy rains, particularly from June to October. Domestic flights are available, connecting Belize City’s Philip S.W. Goldson Airport to San Pedro and Dangriga, but these flights do not service inland sites.

Entry Fees & Guides:

All NICH-managed reserves impose official entry fees ranging from USD 12 to 25. For more details, visit the Belize Tourism Board. Hiring licensed guides can greatly enhance your experience, as they provide expert interpretations of hieroglyphs, architectural features, and the ecological context of the sites. It's important to note that research permits are strictly enforced for academic projects.

Best Time to Visit:

The ideal time to explore these sites is during the dry season, from November to April, resulting in sunny days, manageable humidity, and perfect conditions for photography. It is advisable to avoid peak holiday periods, such as Christmas to New Year, when local resorts tend to be fully booked. Additionally, the shoulder months of May and October can offer lower rates and moderate rainfall.

What to Bring:

Visitors should arrive prepared with sun protection, including a wide-brimmed hat and reef-safe sunscreen, alongside long-sleeved shirts to fend off insects. Sturdy hiking shoes are essential for navigating the terrain, and it is wise to pack water, electrolyte snacks, and extra camera batteries. A lightweight rain jacket can also prove invaluable in case of unexpected tropical downpours.

Gain In-Depth Insights into Maya Civilization Through Their Spectacular Ruins

During the Classic Period (250–900 CE), the Maya civilization achieved remarkable advancements, including the refinement of hieroglyphic writing, which remains the longest pre-Columbian script in the Americas. They also developed the concept of zero within their vigesimal number system. The orientations of temples throughout Belize reveal intricate connections to solar and Venus-cycle observations, which were crucial for their ritual calendars. Extensive riverine trade networks facilitated the exchange of jade, obsidian, cacao, and salted fish between coastal and highland polities, forging essential economic interdependencies across Mesoamerica (Helmke & Awe 2016).

Prioritizing Conservation and Respect for Cultural Heritage

The Institute of Archaeology (IA-NICH) in Belize enforces a strict permit system for both research and tourism activities, overseeing the management of 14 archaeological reserves. To mitigate wear on fragile limestone structures, visitor limits are enforced during peak midday hours, and entrance fees contribute directly to the preservation efforts of these sites. Local guide programs ensure that income generated through tourism benefits the Maya communities directly. In addition, photography restrictions, such as prohibiting flash in mural-rich chambers and preventing climbing on vulnerable structures, are implemented to ensure that these invaluable sites are safeguarded for generations to come.

Explore the Resilience of Today’s Maya Communities and Their Cultural Continuity

Currently, the Maya communities residing in Toledo continue to uphold traditional milpa agroforestry systems that involve rotating crops such as corn, beans, and squash, closely emulating ancient agricultural practices. Additionally, community-based tourism initiatives along the Toledo Maya Cultural Route offer authentic homestays and traditional cooking experiences, effectively linking the preservation of cultural heritage with economic empowerment for the local population (Belize Maya Forest Trust).

Comprehensive Bibliography for Further Exploration

-

Institute of Archaeology, NICH. “Protected Archaeological Sites.” https://nichbelize.org

-

Royal Ontario Museum. “Altun Ha Excavations.” https://rom.on.ca

-

Pendergast, David. Altun Ha: Jade Head Discovery and Context. Museum of Belize, 1979.

-

Awe, Jaime. Archaeological Research in Corozal and Santa Rita. Northern Arizona University Press, 2005.

-

Chase, Arlen & Diane. Xunantunich and Caracol: Temple Sites of Western Belize. UNLV Reports, 2015.

-

Chase, Arlen & Diane. Caracol Archaeological Project Reports. UNLV Reports, 1996.

-

Powis, Terry et al. “Cahal Pech Excavations and Regional Role.” Journal of Maya Studies 12, no. 2 (2010).

-

Mitchell-Hedges, Anna. Mysteries of the Crystal Skull. London: Explorer’s Press, 1998.

-

Helmke, Christophe & Jaime Awe. “Ancient Maya Territorial Organization and Astronomy.” Mesoamerican Research Journal 22, no. 1 (2016).

-

Smithsonian Institution. “Uxbenka Archaeological Project.” Mesoamerican Research, 2021.

-

Belize Maya Forest Trust. “Community-Based Cultural Route.” https://belizemayaforest.org

The Article Ancient Maya Ruins in Belize: Complete Guide to 9 Archaeological Treasures appeared first on Belize Travel Guide

The Article Ancient Maya Ruins: Your Complete Guide to Belize’s Treasures Was Found On https://limitsofstrategy.com